By Morgan Lowe, November 12, 2021

We were always moving on — always a new house and new school. That air of instability makes me anxious to this day. My mother was searching for “safety and a good education,” while I only wanted something that felt like home. I never understood my mother’s decisions until I was in college, which was her goal all along.

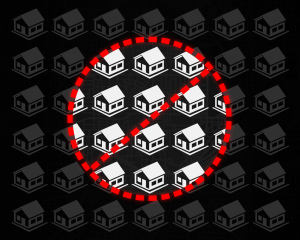

A redlining history lesson

In college I took a course on race relations in the United States. There, I learned the history of redlining, beginning with the National Housing Act of 1934. Following instructions from the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created maps of cities with the specific intention of segregating whites and Blacks. The maps had areas labeled “most desirable” to “least desirable,” with the least desirable neighborhoods set off by red lines. Ultimately, whites moved from undesirable areas into desirable areas, where they could access credit.

Redlining and prejudices tied to home ownership helped spawn ghettos, institutionalized inequality in the housing industry, and created and perpetuated a caste system. Cities redlined in the 1930s continue to struggle with lower life expectancy, air pollution, and food deserts in predominantly Black neighborhoods. And the homeownership rate for Black families is only 44% compared to 73% for white families.

The past is present

The Fair Housing Act (1968 Civil Rights Act) made redlining illegal, but the damage was done. And our government still allows racist lending practices. A 2009 congressional hearing exposed something called reverse redlining. In this practice, banks target communities of color with higher-rate mortgages.

According to testimony, “African Americans earning more than $100,000 a year were more than twice as likely to receive high-cost loans than white homeowners earning less than $35,000 a year.” In fact, while many applicants of color qualified for prime loans, they were pushed into subprime mortgages. Subprime loans don’t just have higher rates — they often have adjustable rates that can increase beyond what the homeowner can afford. Such predatory lending practices forced many to default, contributing to the 2008 mortgage crisis.

That private sector banks take advantage of the American people might not surprise us, but we don’t usually expect the federal government to be part of it.

Corrective steps

Prejudicial policies affect the lives of the victims and their descendants, but they also influence the country as a whole. The financial crisis of 2008 occurred because of the sometimes hidden connections between business, government, and the economy. A failing in one facet of our system eventually affects us all.

So how do we right the wrongs of housing inequality? Experts have suggested that we can increase the minimum wage, regulate the loan industry, and enforce existing laws. Scholars of race relations and government officials (federal, state, local) have called for more federal regulation to prevent discrimination. They also warn about lenders making up their own rules.

One attempt to address housing inequality is the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). This law supposedly provides loan assistance in moderate-income neighborhoods, such as for housing and starting businesses.

Data indicates that the CRA performs well. However, banks provide that data, not the people who should be benefitting from these policies. Numerous studies report on the inner workings of the CRA — assessments of expenses, activities, requests — but even these don’t tell us how effective it is in helping underprivileged communities.

But first . . . campaign finance reform

Redlining is a great example of how the undue influence of special interests can corrupt. That is, our federal government is clearly tied too closely to banks.

During the 2008 housing crisis, Congress remained silent and the banks made their own rules. When asked to regulate, Congress didn’t step up. The relationship between lawmakers and the banking industry is contaminated by dark money and the undue influence of special interests. Congress no longer represents us. Corruption starts at the top, trickles down, festers, and rots. At this point, it’s not a question of asking for what we need. We must collectively demand a government of, by, and for the people.

This is why I volunteer with Wolf-PAC. Our politicians represent special interest groups like corporations and the banking industry, not the people. Only by putting meaningful controls on campaign financing in the Constitution through a 28th Amendment can we right past wrongs, and make the government responsive to We the People. Only by addressing the undue influence of special interests, can we really address issues tied to inequity, inequality, discrimination, and race in the U.S. Please join us!

Acknowledgments

Wolf-PAC is driven by volunteers freely donating their time. This work is brought to you by the Communications Team.

- Editing by Karen Chambers, Brian Martel, and Kristine Baumstark

- Graphics by Michael Grilli

Sources

- Brown, K. J. (2020, July 23). $24 Minimum Wage Is What It Takes To Afford Rent Anywhere in America. Well + Good. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.wellandgood.com/minimum-wage-affordable-housing/

- Denning, S. (2011, November 22). Lest We Forget: Why We Had A Financial Crisis. Forbes. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/11/22/5086/?sh=2b60cfdef92f

- Husain, A. (2016, November 2). Reverse Redlining and the Destruction of Minority Wealth. Michigan Journal of Race and Law. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://mjrl.org/2016/11/02/reverse-redlining-and-the-destruction-of-minority-wealth/

- Mother Jones. (2008). Where Credit Is Due: A Timeline of the Mortgage Crisis. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2008/07/where-credit-due-timeline-mortgage-crisis/

- Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. (2021, February 9). Community Reinvestment Act: Bank Type Determinations, Distressed and Underserved Areas, and Banking Industry Compensation Provisions of the June 2020 CRA. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.occ.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2021/bulletin-2021-5.html

- Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. (n.d.). Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) Ratings and Performance Evaluations by Month and Year. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.occ.gov/topics/consumers-and-communities/cra/perfomance-evaluations-by-month/index-cra-ratings-and-performance-evaluations.html

- Richardson, B. (2020, June 11). Redlining’s Legacy of Inequality: Low Homeownership Rates, Less Equity For Black Households. Forbes. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/brendarichardson/2020/06/11/redlinings-legacy-of-inequality-low-homeownership-rates-less-equity-for-black-households/?sh=3363a2842a7c

- Rothstein, R. (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing.

- The Digital Scholarship Lab and the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. (n.d.). Not Even Past: Social Vulnerability and the Legacy of Redlining, American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers. The Digital Scholarship Lab and the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://dsl.richmond.edu/socialvulnerability/

- U.S. Government Printing Office. (2010). Predatory Lending and Reverse Redlining: Are Low-Income, Minority and Senior Borrowers Targets for Higher-Cost Loans? Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg54512/html/CHRG-111shrg54512.htm

- Williams, J. P. (2019, May 24). Air Pollution Rates Higher in Historically Redlined Neighborhoods. U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2019-05-24/asthma-air-pollution-rates-higher-in-historically-redlined-neighborhoods

One thought on “Redlining and the Undue Influence of Special Interests”